The Nature of Suiseki in Japan - by Wil in Japan

|

"The Nature of Suiseki in Japan"

by Wil in Japan

Wil, author of this article, is one of NSA's (Nippon Suiseki Association) Directors, and he was nominated by the NSA Board to present his paper at the 8th World Bonsai Convention ~ Saitama City, Japan on 2017 April 30. I am very grateful to him to allow me to share, through these pages, his work with all those people who were unable to attend, about because this text seeks to clarify on a very current topic : a suiseki is a natural stone or not ? What follows is the original text presented by Wil at the Saitama Convention.

|

|

| Like many people from the West, my first in-depth knowledge of suiseki came from English language sources, and as I was to find out later, much of what I had learned was exaggerated, over simplified, or downright incorrect. It is often the case that information being transferred from one culture to another, between languages that are otherwise completely incompatible, becomes obscured as the crucial details and nuances are lost in translation. It is like a game of Chinese whispers or making a copy of a copy of a copy – with time and space, any resemblance to the original is gradually lost. |

|

|

The most widely read English language book on the subject of Japanese suiseki is by far The Japanese Art of Stone Appreciation: Suiseki and its Use with Bonsai, co-authored by Vincent T. Covello and Yuji Yoshimura. It was first published in 1984, and has been through numerous reprints and re-editions.

It is the earliest and most influential English work on the subject, and it provided the foundation for numerous other books to follow, and countless more websites made by aspiring experts or clubs seeking to inform their members.

Little by little, as the narrative was repeated time and time again, the text, which was already largely problematic, slowly became less accurate, and further from the reality of how suiseki and stone appreciation are actually practiced in Japan.

Further compounding the problem, the vast majority of people in the West writing or repeating other people’s texts on the subject, have spent little if any time in Japan, and do not speak the language to have real access to primary sources or experts in the field. Now over thirty years later, the over-simplified version of suiseki first delivered to the West has been largely accepted and become hard truth, making new or more advanced understandings difficult to accept for many.

|

|

|

As a first step toward remedying this situation, Dr. Thomas Elias and his wife Hiromi Nakaoji last year published two ground-breaking articles on part of the reality of stone appreciation in Japan.

They have a vast library of Japanese language books and reference materials on the subject, and more importantly, the language skills to access them. They revealed sources that openly discussed the mechanical manipulation of stones to not only fix uneven bottoms, but to enhance the shape of stones and improve their landscapes.

They supplemented their first text-based study with an article detailing a visit to one of Japan’s leading stone carvers, who shared with them his workshop and demonstrated the techniques he used to either improve or completely make suiseki. They published pictures of his workshop, machines, and examples of Japanese suiseki that were completely manmade.

For the majority of their readers this revelation either came as a shock, or confirmation of something they had long suspected, but had no evidence of. Many people could not believe that suiseki were openly made in Japan. In fact, it is a very delicate subject in Japan as well, but it is the opposite of everything that people in the West have been told.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Covello and Yoshimura define suiseki in the very first sentence of their book as:

“Suiseki are small, naturally formed stones admired for their beauty and for their power to suggest a scene from nature or an object closely associated with nature.”

|

| This has been repeated and reworded countless times over, and many clubs in Europe and North America firmly believe that if a stone is not 100% natural, then it CANNOT be appreciated as suiseki. In light of their evidence, however, Elias and Nakaoji reached the conclusion that the West got it wrong and this definition was incorrect. They state that the manufacturing of stones has been openly practiced and accepted in Japan since the 1960s, and that suiseki were not defined as natural stones in Japan. Unfortunately, a great deal of evidence to the contrary was overlooked in reaching this conclusion, and the result has been somewhat scandalous. Again, to most people in the West, this came as a shock, and a direct contradiction to all they had been told. While some people do not seem concerned, many now feel that Japanese stones cannot be trusted. The loudest opponents claim now that Japanese suiseki are a fraud- they are all lies and fake, and I understand that at least one European club is considering an outright ban of Japanese stones in their exhibitions. They now believe that all Japanese stones are manufactured, and therefore not true suiseki. People have been left confused and upset, and this refined tradition is now being criticized worldwide. |

| To say that the reality of Japanese stone appreciation has been somewhat misrepresented in the West is true, but to say that this reality has been openly discussed and accurately expressed in Japan would not. |

|

Stone appreciation in Japan has evolved over the course of many centuries, and as with any tradition, it has undergone various changes and developments to get where it is today. In truth, however, this evolution is long, complicated, and requires historical source material that is difficult to access in order to articulate and understand well. Though my efforts will surely fall short, it is my goal here to give a concise historical overview of the evolution of stone appreciation in Japan, with particular attention being given to the concept of “nature”. Must a stone be natural to be considered suiseki? Is it the nature of stones themselves we are meant to appreciate, or is it the grander whole of nature we are meant to appreciate using stones as a vehicle. Is it both? Or are they even separable in the first place?

|

|

In its long history, stone appreciation in Japan has never been a singular, unified practice nationwide, with formalized schools or styles that have stood the test of time, such as those you see in the tea ceremony or flower arrangement. Though incidental mention of stone appreciation can be found in Heian period (794 – 1185) courtier diaries and poetry, no such treatise on “the way” of stone appreciation is known from this early time. The earliest physical evidence of stone appreciation is to be found in painting, specifically in illustrated handscrolls from the Kamakura period (1185–1333).

|

| “The Illustrated Tale of the Monk Saigyo” (detail), ca.1260 |

|

“The Miraculous Tales of the Deities of the Kasuga Shrine” (detail), 1309 |

|

|

|

|

The first is from the Saigyōmonogatari emaki, or “The Illustrated Tale of the Monk Saigyo”, which is attributed to Tosa Tsunetaka (dates unknown) and believed to date from around the year 1260.

Illustrated in the scene of interest is nothing like contemporary suiseki, but rather what was called a sekidai, or literally “stone pedestal”. It is located out-doors on an elevated platform, just off the veranda so it could be viewed easily from indoors. Stylistically it is far closer to multiple bonsai rock plantings arranged together to form a miniature landscape scene, similar to modern day bonkei.

|

|

Perhaps the most widely known and well-published painting of such an arrangement is from the Kasuga gongen genki, or “The Miraculous Tales of the Deities of the Kasuga Shrine”, completed by court painter Takashina Takakane (dates unknown) in 1309.

This is very similar in that we have an elevated platform situated just off a veranda with a bonkei-like arrangement at eye level from the perspective of those inside. Two remarkable differences are that the arrangement appears to be within a portable wooden tray with carrying handles on each end, and most remarkably, there are two separate stones displayed beside it. Both appear to be in ceramic containers, one perhaps in water, and the other in fine white gravel.

|

|

| We need not spend much time on this, but more evidence of this outdoor style predecessor of modern stone appreciation can be found in the 1351 handscroll Bokie, or “The Story of Kakunyo”. |

| |

|

| |

“The Story of Kakunyo” (detail), 1351 |

|

| Here we can see both a portable bonkei-like arrangement and a single stone in a ceramic container. This time note that they are on the veranda rather than a raised pedestal in the garden. We see here a slight move toward bringing the stones indoors, but unfortunately no stones verifiably from this period in medieval Japan are known to exist. |

| Interestingly, however, is a mid 14th century treatise on bonseki by Rinzai Zen monk Kokan Shiren (1278–1347). This text is widely celebrated as one of the earliest and most revealing discussions of stone appreciation in Japanese history (the majority of which can be found in English online). He does not state clearly whether he appreciated stones indoors, but what is interesting is that he explicitly states that he placed stones in celadon trays with white sand at the bottom, just as depicted in the Kasuga gongen genki and Bokie, which were completed around the same time Shiren was writing. |

|

|

|

| Stones displayed in celadon containers |

|

|

This is the first description of stones being appreciated in-and-of themselves, not as part of a seki-dai bonsai rock planting, or other such arrangements. The text is fascinating and deserves a detailed study, but the two key points for our purposes are:

|

|

1) Shiren states that he used children to gather his stones, so we can assume that he appreciated stones taken directly from nature: “So I had the children gather up stones in the corner of the wall. I brushed them off and washed them, preparing a green celadon tray with white sand on the bottom. The result was poetry that would lighten your heart. The landscape lent a coolness to the air and dispelled the heart.”

2) In the description that follows the above entry he extols the virtues of bonseki as he practices it, but not once does he discuss the stones themselves: “These stones then, just a number of inches tall, and this tray roughly a foot across, they are nothing short of a mountainous island rising from the sea! Jade-green peaks penetrate the clouds and are encircled by them. A blue-green barrier, immersed in water, is standing straight up. There are caves as if carved in the cliff sides to hide saints and immortals. Jetties and spits flat enough and long enough for fishermen. The paths and roads are narrow and confined, yet woodcutters can pass along them. There are lagoons deep and dark enough to hide dragons”.

|

| His focus is entirely on the viewing experience and the imaginative process behind it. It is about the beauty of nature, and the power of a simple stone to transport the viewer to another world. Nowhere does he discuss the minutia of the stones themselves, or focus on the fact that the stones must be natural. In this sense, it is not the “appreciation of stones” as such. He is not contemplating the forces of nature that shaped the stone, or admiring its geological characteristics. It is, on the other hand, a gateway to an idealized, natural land that is part reality and part fantasy. It is an act of escapism from the toils of everyday life, to a place where the mind is set free to explore its own depths. It is a spiritual exercise with echoes of the cosmic perspective that inform Buddhist thought. |

| Shiren’s writings on the subject would continue to shape how bonseki was practiced for generations to come, and one of the next major writings on the subject known to us today comes some 100 years later. |

|

The Setsuyōshū is a dictionary compiled between 1444 and 1474 by Rinzai Zen monks of the temple Ken’ninji in Kyoto. It includes an entry called the Bonsan jittoku, or “The Ten Virtues of Bonsan”, which is defined as follows:

It enriches the spirit and prolongs happiness.

It relaxes the eyes and relieves fatigue.

It cleanses and purifies the heart.

You can feel the seasons in the trees and grass.

You can look upon grand vistas without traveling far.

You can enter caves without moving.

You can gaze upon the sea without visiting it.

You can escape the heat of summer and feel cool.

Though years may pass you will not feel aging.

A person who loves this knows no wrong. |

|

Mention of trees and grass in this entry implies that bonsan, as used here, refers more to bonsai rock plantings, like the sekidai previously illustrated. The interchanging use of the terms bonseki and bonsan over the years has caused a great deal of confusion, but they were closely related and largely approached in the same manner. Of note for our purposes is that again, in this Zen writing there is no discussion of whether or not the stones themselves must be natural. The text is concerned with the physical and spiritual benefits of appreciating bonsan, and elaborates on the beauty of the natural world that can be detected therein.

|

|

Interestingly, the authorship of the Bonsan jittoku is attributed to the Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi (722–846), who was well known for his love of Chinese Taihu stones. As the historian Marushima Hideo points out, however, the Bonsan jittoku made a sudden appearance in Japan at this time, and with no precedent in the Chinese record, it is thought that the attribution was invented by the Japanese author, most likely in an effort to boost the entry’s authority on the subject. Considering Bai Juyi’s fame as a collector and connoisseur of stones, his inclusion here indicates that there was a certain awareness of Chinese stone lore in Japan at the time, and it is no coincidence that the name of a famous Chinese historical figure would have been used then, when the warrior elite fetishized Chinese material culture.

|

|

In fact, it is during this time that the earliest evidence of stones clearly being appreciated indoors appears. Bonseki could be found in the tearooms and living spaces of wealthy daimyo. Records of stones in this context take a slightly different tone, however, and they shift toward becoming objectified, highly prized objects, particularly those said to be of Chinese origin. One particular work that well illustrates their place in the world of the Muromachi military elite is the Kundaikan sōchōki.

|

| Though the work is attributed to Nōami (1397–1471) and his grandson Sōami (?–1525), a number of copies exist, and each reflecting differences in text and illustration, it is difficult to identify which may have been the original and exactly who was its first author. Still, there is little doubt that it originated in the early 16th century, and it offers a detailed glimpse into the way the most valued objects in daimyo collections were displayed and appreciated. |

|

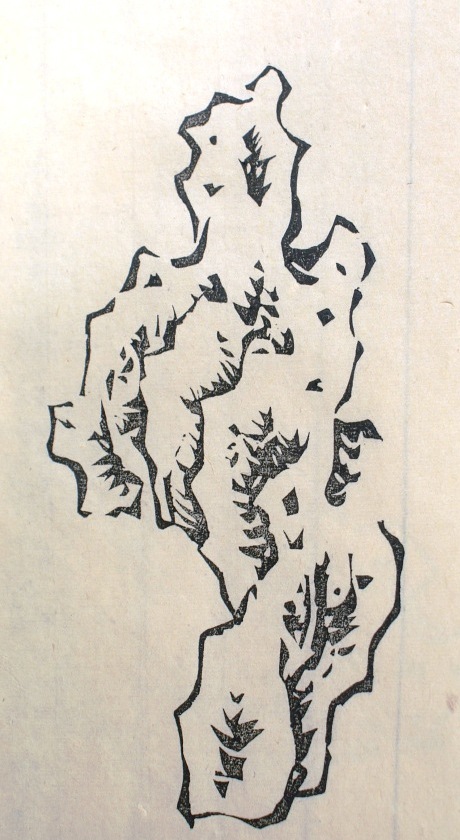

Kundaikan sōchōki (early 16th century)

The scroll is divided roughly into three sections: names of Chinese painters and evaluations of paintings brought from China, explanations and methodologies for the decoration of rooms, and evaluations and appraisals of other objects brought from China, mainly ceramics, lacquer-ware, and bronzes. With numerous copies extant, it is thought that the work was reasonably widespread, and it served not only as an important text for the ways in which to decorate formal space, but also as a connoisseurship guide that informed its readers of what was thought to be good or valuable in terms of imported art and luxuries. Bonseki are featured in each and every known example of this handscroll, some of which appear to be little more than rough sketches.

|

| Mon’ami kadensho (16th century)6th century) |

|

|

|

Surely, considering the elite audience these scrolls were intended for, only the best materials were included and evaluated, and they also illustrate trends in terms of which artists or what sort of decorative objects were popular at the time.

It is here for the first time in Japanese history that we see individual stones being objectified and appreciated not for their inherent ability to provide spiritual benefits and an escape to the natural world, but for their origin and value as imported art objects. In fact, two of the most celebrated stones remaining from around this time are said to be of Chinese origin, and reflect the shift in stone appreciation that was taking place then.

|

|

The first is the bonseki Yume no Ukihashi, or “Floating Bridge of Dreams”, currently housed in the Tokugawa Museum in Nagoya. It is said to have been owned by Emperor Godaigo (1288–1339) at the end of the Kamakura period, although scholars and historians doubt this legendary history. Nevertheless, the Ming dynasty bronze tray and white gravel display reflect the tastes of the Higashiyama meibutsu culture illustrated in the Kundaikan sōchōki, and we could easily imagine it displayed in that context, such as illustrated in the Muromachi period illustrated handscroll, Shūhanron, attributed to Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559) in the 16th century. What is important to note is that the stone is said to be of Chinese origins, specifically from a mountain in Jiangsu province, the importance of which we will return to later.

|

|

|

|

| Yume no Ukihashi – “Floating Bridge of Dreams” |

|

Shūhanron (16th century) |

|

| |

|

Another important stone from this time is the bonseki Sue no Matsuyama ,“Eternal Pine Mountain”, currently housed in the temple Nishi Honganji in Kyoto. As with the previous stone, this one too has a long history whose earliest origins need not be debated here, but what is certain is that its history in the Nishi Honganji temple begins in 1553. It too is said to be of Chinese origins, purportedly from the temple Jingshansi in Zhejiang province.

|

| Sue no Matsuyama – “Eternal Pine Mountain” |

|

|

| If indeed from China, both of these stones would have been cherished and revered as rarities imported from the continent, and therefore valued differently from the way the natural stones admired by Zen monks discussed earlier were valued. In fact, it is at this time that we first encounter the phenomenon of giving stones poetic names from Japanese literature. They were carefully stored in boxes, and recorded prominently in records of tea gatherings. So cherished were these imported stones that the warlord Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) had a space dedicated for them in his castle on Azuchiyama, which although now lost, we know from architectural records. The appreciation of bonseki had changed from a contemplative one focused on nature, to venerating them as precious imported objects with valuable origins and historical pedigrees. What’s more, we know that in Chinese practice stones are openly altered and worked to improve their appearance. |

|

Floor plan for Azuchi Castle.

Note the space dedicated for bonsan display highlighted on the left |

|

| In modern-day Japan, with an emphasis being put on the question of whether or not a stone is natural, it has become impossible to discuss alterations potentially done to historically important stones. It is almost considered rude or insulting to the stone to suggest that they are anything other than natural. Therefore, what follows may not be popular with many people in Japan, but it is time to face the facts. Both of these stones have been displayed at the Nippon Suiseki Association’s Meihinten exhibition, and both have been carefully examined by NSA officials and publishers at the time. The people who examined them in preparing for the exhibitions have reported that both stones show signs of having been worked. We know that altering stones has always been common practice in China, and we know too that Japanese literature on bonseki up until this time was not concerned with whether or not a stone was natural. The historical context would therefore certainly have allowed for stones to be worked, and reliable sources in the stone community who have examined them verify this. In fact, ambitious readers now have the chance to form at least a partial opinion, as Sue no Matsuyama is currently on display at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno, featured in their exhibition on the tea ceremony (until June 4, 2017). |

|

The stone has a patina unlike any other, and it is displayed in the sahari bronze tray it is always accompanied by. I would encourage all of you to go and look at this stone. Look at its lower edge and the gap between the stone and the tray, and consider for yourself whether you think the stone’s base has been worked. And then, step back and look at it as a whole one more time. Look at the landscape it represents, imagine the centuries of history it has seen to acquire its outstanding patina, and the elite historical figures who have admired it. Explore the literary allusions contained within its name and consider the cultural context in which it was born. Does it matter if the bottom might have been worked? Does that detract from its potential to inspire and move its viewers? It was completely irrelevant to people then, and should not matter to us now either.

|

Bonseki continued to evolve throughout the Edo period and many of the stones that remain from this time show clear evidence of having been altered or even completely manufactured.

One of the most important arbiters of taste in the early Edo period (1615–1868) was Kobori Enshu (1579–1647). He was an architect, a garden designer, a famed artist and flower arranger, tea master to the third Tokugawa shogun and creator of his own school of tea, and a bonseki enthusiast and practitioner. A number of his stones remain today, and a close look at them reveals a great deal about bonseki practice at the time.

Let us first look at the stone called Hatsukari, or “First Goose”, currently housed in the Tokugawa Art Museum.

|

| Hatsukari – “First Goose” |

|

It is said to be from the Kamogawa in Kyoto, and is a soft mountain form with two overlapping peaks. Its name, which is a poetic term referring to the first goose one sees flying south in the autumn, is clearly derived from the white bird-shaped pattern visible on the right.

For many years we have been told that stones must be natural in Japanese practice, so what should one think when encountering this historically important bonseki? When asked, a leader in the field once said, “Yes, this stone is 100% natural. It is amazing how nature can create such things.” Please look for yourself. Do you think this stone is natural? That taken into account, in Enshu’s bonseki practice was it the geological forces of nature that shaped the stone that mattered, or was it a stone’s ability to poetically allude to nature and inspire viewers? |

| Another stone owned by Kobori Enshu was the bonseki Rafuzan, or “Mount Luofu”, named after the sacred peak in China’s Guangdong province. |

| Rafuzan – “Mount Luofu” |

|

This stone is kept in the Nezu Museum, and is often displayed on a sahari tray like Sue no Matsuyama. It is said to be of Chinese origin, and a close look at its shape and texture reveals a surface that is so smooth it glistens, almost as if it has been heavily polished. Is this stone natural?

In modern times, suiseki have been defined as natural stones, but this modern definition need not apply to 17th century bonseki. In some instances opinions are so strong that it is considered rude to suggest that a stone might not be natural, but it is simply not relevant in the case of historical stones like this. Nowhere in the literature of the time or among the stones that remain from then can we find evidence that the natural state of a stone was of paramount importance. In fact, examining stones from this time which have been clearly manipulated reveals that the question was irrelevant even at the highest levels of practice, as represented by Enshu, who was instructing the Tokugawa shogunate in the tea ceremony. |

|

|

Just over 100 years after Enshu’s time, in the fourth month of 1772, the two-volume Bonsan higon, or “Secret Transmissions on Bonsan”, was published in Kyoto, offering guidelines and instructions to bonseki enthusiasts.

It is said to contain information passed down by Hasegawa Genzaburo (dates unknown), who was close to the powerful military leaders of the Muromachi and Azuchi/Momoyama periods who cherished bonseki as part of their meibutsu collections.

It states that stones in the shape of Mount Fuji are considered best, and gives specific dimensions for stones, stressing that they should ideally be natural, referring to stones that have been altered as “dead stones”. This is one of the first known mentions in Japanese literature that explicitly states that bonseki should be natural.

|

|

Bonsan higon

“Secret Transmissions on Bonsan”

|

|

|

|

| However, there remain countless bonseki from the Edo period with perfectly smoothed shapes that resemble mountains and seem nothing less than sculptural. Some are formed in such a way that they take advantage of natural mineral striations in the stone to resemble clouds or snow remaining on peaks. |

| Edo period bonseki |

|

| Some seem completely made, such as the examples owned by Kobori Enshu and the stone above, while some show only partial signs of being altered, such as the bonseki displayed in the World Convention exhibition, Koharu Fuji, or “Little Spring Fuji”. |

| Koharu Fuji – “Little Spring Fuji” |

|

| The accompanying handscroll features a painting of the stone by haiku poet and follower of the Matsuo Basho style, Yoshida Hakuma (1720–1786), and it is dated the second year of the Tenmei era (1782). |

| Handscroll accompanying Koharu Fuji, by Yoshida Hakuma, 1782 |

|

|

This stone and handscroll are important pieces of evidence that illustrate the culture of the time. A number of poems describing the stone are featured in the scroll, some using the word bonseki, some bonsan, and others Fuji ishi. We can see here that the words were used more or less interchangeably at this time, and a look at the bottom of the stone clearly reveals that it has been slightly worked in places so that it can sit appropriately.

|

|

The physical evidence from this period shows clearly that at even the highest levels of practice, the question of whether a stone was natural was not first and foremost. It is clear that in this period, what is most important is the allusive power of the stone – its beauty and resemblance to an idealized mountain, its ability to call forth poetry in the viewers and provoke a certain cultural memory. Bonseki were not appreciated at this time for being naturally formed stones. The fascination was not with the stones themselves as natural wonders, but rather in their ability to allude to natural scenes and even specific places, like Mount Fuji or sacred mountains in China that people would have only known from imported poetry or painting.

The Bonsan higon’s mention of worked stones being “dead”, however, clearly does not reflect actual practice, but rather the ideas of the author (whose claim to be transmitting information from the Muromachi period is immediately questionable because of statements such as “stones in the shape of Mount Fuji are best” – an idea that certainly was not in the minds of those who admired imported Chinese stones, or named them after mountains in China). Rather, this idea seems to reflect a newly emerging interest in stones as natural objects.

This new perspective on stones as natural curiosities emerged in the late 18th century, and would go on to change stone appreciation in many ways. In 1773, only one year after the Bonsan higon was published, this new perspective found expression in the Unkon shi, or “Stone Manual”.

|

| Unkon shi – “Stone Manual” |

|

Though there were Chinese precedents, this was Japan’s first stone catalogue, and it is clear that its author, Kinouchi Sekitei (1724–1808), was interested in a variety of stones, but not particularly traditional bonseki.

The book is almost entirely text based, and documents stones that Sekitei had either seen or collected over many years of traveling the country. His commentary consistently begins with descriptions of the geographic origins of each specimen, and includes details on the shapes, colors, textures, and hardness of the stones, at times even taking a utilitarian approach, discussing the stones’ usefulness in tool making or building. He occasionally even mentions people he met along the way in his travels who should be consulted if the reader wanted to visit these places and investigate the rocks themselves. |

|

|

There is only a very short passage on bonseki, stating that they were treasured in ancient times, though in the middle ages they had fallen out of fashion and had only in recent years begun to be revisited. He mentions a few well-known examples, but for our purposes the following comments are of interest :

“The size of the stones are fixed, and those with snow on the peaks, or with valleys, waterfalls, caves, foothills, cliffs, and walkways naturally occurring, are considered the best. In the temple Raigoji in Sakamoto, Omi province, there is a stone called Kusen hakkai, or “Nine mountains, eight seas”. It is bigger than most bonsan. […] There is no specific place from which bonseki are collected.”

At the end of his definition and description, he acknowledges the need for a separate discourse on bonseki and its display, but does not expand further (note he uses both the words bonsan and bonseki in the above passage). His comment that stones with “naturally occurring” features are best is consistent both with his own practice and the Bonsan higon, but it is clear from his brief treatment of the subject that it was not of particular interest to him. Sekitei was interested in natural stones in a number of ways, but was his lack of interest in bonseki due to the fact that many were indeed NOT natural?

His interest was in kiseki, which could be thought of as “strange”, “odd”, or “unique” stones. This was a new development in Japan at the time. The illustrations in his book are at times like those you would expect to find in natural science studies: detailed, realistic representations.

|

|

|

Portrait of “Stone Master” Sekitei

|

|

|

Sketch of a chalcedony specimen

from Sekitei’s collection

|

|

| |

|

But they also reveal influence from Chinese book Suyuan shipu, which was first published in 1613, and is known to have been in the collection of bibliophile Kimura Kenkadō (1736–1802), who was a close friend of Sekitei’s. Here we have for the first time in the Japanese record examples of naturally occurring figure stones, such as the so-called “Buddhist figure stone” that could be seen in a valley near Mount Fuji, which is remarkably similar in its execution to the Suyuan shipu’s “Bodhisattva stone”.

|

|

Boshisattva Stone”

from Unkon shi

(at left) |

|

|

"Buddhist Figure Stone”

from Suyuan shipu

(at right) |

|

|

|

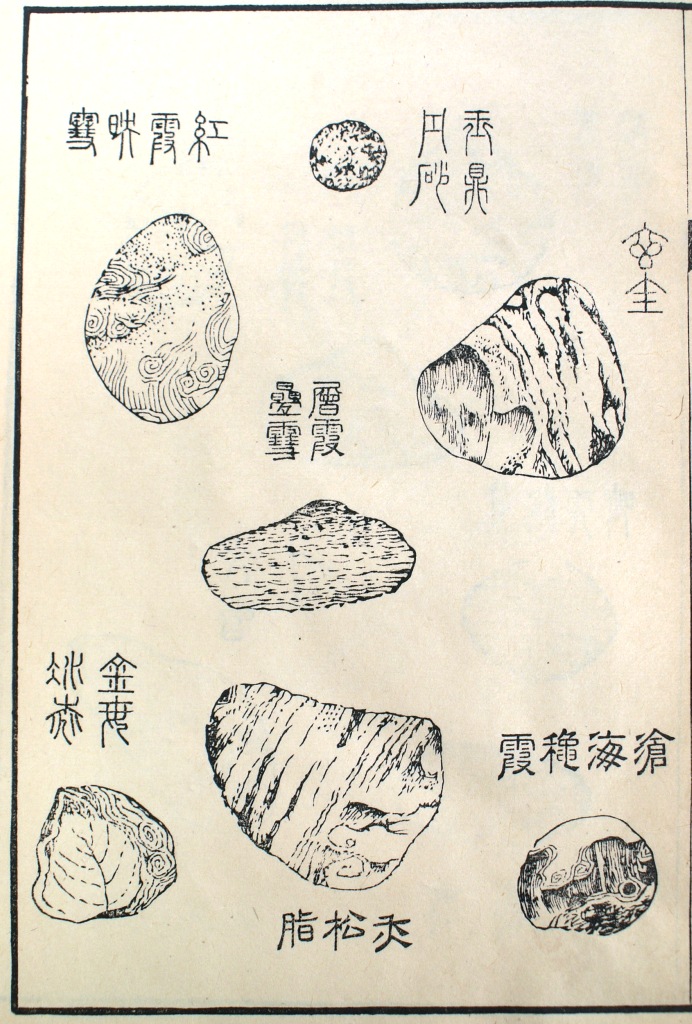

| Pattern stones also appear here, perhaps for the first time in the Japanese record. The Suyuan shipu illustrated numerous small stones with interesting patterns, and Sekitei did the same in his book as well, following a very similar format. |

|

|

|

Pattern stones from

Unkon shi |

|

Pattern stones from

Suyuan shipu

|

|

|

Figure stones and pattern stones are now commonly appreciated in the suiseki world, but that was not always the case. Sekitei’s late 18th century work is where they first seem to appear, and his interest in naturally occurring stones would go on to have a profound impact on the way stones were to be appreciated in Japan. Kiseki had at this point emerged as a separate phenomenon from bonseki, and the way the terms were defined would continue to evolve, long before the word “suiseki” would even appear in the world of Japanese stone appreciation.

In Meiji 43 (1910) the first issue of “Koseki shi” was published. This was Japan’s first periodical dedicated to the appreciation of stones, and its focus was heavily on the type of kiseki that Sekitei admired. In the first issue, it clearly defined six different types of kiseki :

Kaiseki : Literati-inspired stones such as Lingbi, Taihu, and Ying stones that are displayed in tokonoma. [What we would today call Chinese scholar’s rocks.]

Tenseki : Stones used for bonsai rock plantings.

Suiseki : Stones that can be placed in suiban.

Bonseki : Stones used with patterns or shapes made in pebbles and sand on lacquer trays.

Ten’nen kiseki : Unique, natural stones that resemble landscapes, figures, Buddhist sculptures, animals, and so on.

Kaseki : Natural things that have turned to stone. [Fossils]

This is interesting for a number of reasons. |

| Bonseki, which was once used interchangeably with bonsan to refer to largely mountain shaped stones displayed in ceramic or bronze trays, now clearly only referred to stones used on black lacquer trays with designs drawn out in white sand, such as we see today. |

|

| Modern Hosokawa school bonseki display |

|

Suiseki is here found in print for one of the first times in its modern usage, and it is clearly an abbreviation for “suiban seki”, or stones displayed in suiban. This would have likely included the historical bonseki Yume no ukihashi and Sue no Matsuyama that were discussed earlier. Published examples from around the time labeled “suiseki” show that the meaning of the word may not have been universally agreed upon, as today certainly we would consider this particular display closer to bonkei.

The requirement for a stone being natural is emphasized only in the definition of kiseki, which is strongly reinforced by calling them ten’nen kiseki, or “natural kiseki”. This definition sounds very much like the definition we hear for suiseki today. At this time, however, one of the strongest points of contrast is that kiseki were largely displayed on daiza, as opposed to suiseki, which were displayed in suiban. Another point is that figure stones are included and singled out as particular types of kiseki, but they do not feature in the definition or any of the illustrations of suiseki.

|

|

|

| |

|

“Suiseki” from Kenshun’en Bonsai

Picture Album, by Yamaoka Sentaro, 1918 |

|

|

|

|

While the definitions are clearly distinct here, they would go on to merge in various ways moving forward. The groundwork for a new definition of suiseki was laid in 1934, with the publication of “A Discussion of Suiseki” by Chubachi Yoshiaki.

He was considered the greatest authority on the subject in the early 20th century, and published often in the magazine “Bonsai”, which was published by the great bonsai master who founded the Kokufu exhibition series, Kobayashi Norio.

As part of his discourse, Chubachi compares and contrasts bonseki and suiseki, in an effort to clarify how they differ from one another. He says clearly that they are difficult to completely separate, as both are displayed in tokonoma or zashiki as arts that recreate the beauty of nature.

In his discussion of bonseki, he notes that it has a long and venerable history, with various different schools that have clearly established rules. He says that when faced with a bonseki display the viewer will certainly feel that it is beautiful, but gazing for long will certainly lead one away from the true beauty of nature, into more of an idealized beauty. It is more literal and explicit, an attempt at a “true” representation of the desired scene, and stones are often fabricated to represent this idealized scenery. He likens bonseki to richly colored landscape paintings, which may be beautiful, but lack a certain depth in terms of revealing the true beauty of nature.

In contrast, for Chubachi suiseki are more like monochrome ink paintings. They are figurative and implicit, and have an “emptiness” about them that is more open to interpretation, and therefore they have greater depth in terms of representing the true beauty of nature. He also notes that it has a very young history, with no established schools or fixed rules, but that was NOT to say that it was a completely open ended pastime to do however one pleased.

He states: “Bonseki is a realistic expression of natural landscape scenery that approaches idealism, whereas suiseki uses a part of nature itself (an unworked, natural stone) to express natural landscape scenery.”

He states repeatedly and in many different ways that suiseki MUST be all natural stones, and that no manmade alterations were acceptable. If the bottom or back of a stone were altered, or if an ideally shaped part of a larger stone were removed for appreciation on its own, then it could not be suiseki in his view. He was trying to create something new, and distinguish it from the bonseki of the past.

Written only 25 years after the Koseki shi gave basic definitions for many types of viewing stones, Chubachi released views that went much further. While the Koseki shi focused primarily on ten’nen kiseki being all natural stones, Chubachi all but removes the word kiseki from his discussion, using the word in only one paragraph to describe the Chinese stones admired by literati in the pre-modern era. It is apparent from the illustrations in his book that he coopted natural kiseki into his definition of suiseki, and now, for the first time in print that would be accessible to a wide audience, he stressed repeatedly and without compromise that stones MUST be all natural to be considered suiseki. It is interesting too to note that, while his definition of “suiseki” is still “stones displayed in suiban”, his illustrations include many stones on daiza that would have previously been thought of as kiseki, but are now, unaware of the linguistic contradiction, included in a discussion of suiseki

|

|

Murata Kenji, who helped pioneer the stone boom of the 1960s and 70s, repeated this definition in his 1959 publication “Bonsai Pots and Suiseki”.

In fact, as a relatively new author he quotes Chubachi directly in many passages to lend the definition authority, as if it were being handed down by an old master. He repeats Chubachi’s insistent claim that suiseki must be natural stones, but he goes even further in expanding on Chubachi’s definition. Murata is the first to include the idea of appreciating suiseki for their patterns or colors, and specifically makes the case for chrysanthemum stones from the Neo Valley in Gifu Prefecture, and the akadama stones of Sado Island. He also includes what had been previously labeled kiseki as a sub-category of suiseki, and brings stones displayed on daiza under the suiseki umbrella as well.

This book was re-issued at least six times, and the section on suiseki was not only expanded in later editions, but it was also published separately as an individual pamphlet for even broader distribution. This publication served as one of the catalysts for the stone boom of the 1960s and 70s, and it influenced future publications for many years to come.

|

|

|

| |

|

Bonsai Pots and Suiseki,

by Murata Kenji, 1959 |

|

| |

|

|

Chart classifying viewing stones by Murata Kenji (1959). This marks the earliest published use of the word “suiseki” to take on the

broader meaning of “elegant stones” (gaseki), which included suiban stones, daiza stones, and kiseki (here defined primarily as figure stones).

|

| |

|

However, there was a certain reality that could no longer be denied. Both Chubachi and Murata insisted that suiseki be all natural stones, more than anything perhaps as a way of differentiating the new pastime from traditional bonseki. But in truth, Japan already had a culture hundreds of years old of enhancing stones to bring out their natural qualities, or even completely shape their contours. Examples of all types of stones remain from before their time- both completely natural, and completely made, and the vast spectrum of partially worked stones in between. No 20th century invention of new rules could eliminate this, despite efforts to ignore it.

Instead, stone carvers became more conscious of “naturalism” in their work, and efforts were made to eliminate traces of man’s hand. Careful examination of early bonseki reveals that this was not such a concern in the past, as chisel and grinding marks are often clearly visible, but now the rules had changed. Because of this new mentality, speaking openly about whether stones had been worked or not became taboo, and the subject was all but ignored. It is now rude to discuss, and an unofficial “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy took form. Big money was now involved, and worked stones were deemed less valuable than natural stones under this newly invented set of rules.

|

|

As the stone boom picked up momentum, countless guides were published detailing where stones could be collected, and people flocked to the rivers and mountains in search of stones that could be admired as suiseki. It should go without saying, however, that as demand increased, the supply of quality stones was only bound to decrease. It was during this time that full-fledged suiseki dealers emerged. Throughout the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods, suiseki were handled primarily by bonsai gardens, and as we know, bonsai professionals make and create things for a living. As they are in the business of creating beautiful objects, it should come as no surprise that there was little objection on their part if a stone was worked to improve its beauty. Bonsai gardens had always sold both natural and worked stones, though now with these new rules in place, it was impossible to speak about openly.

If you look at exhibition catalogues from the time, you can see that there are plenty of natural stones in suiban (Chubachi’s definition of suiseki), but you also find stones that are most likely not completely natural. Yet all of these things were now being labeled as suiseki, whether they were natural or not (Chubachi would have considered worked stones bonseki, not suiseki). As it became clear that there was no way of denying the fact that cut and even worked stones were being displayed in Japan’s premier suiseki exhibitions, the issue had to be addressed. In fact, Juseki magazine, the leading publisher on suiseki at the time (owned and managed by the Murata family), openly advertised and endorsed “suiseki finishing machines”, which came with both grinding and polishing wheels for working the surface of stones.

“Suiseki Finishing Machine” (1960s promotional pamphlet), Endorsed by Juseki magazine and the International Meiseki Club --->

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In light of the reality of exhibition standards, market demands, and the content of their own publications, it was impossible to pretend any longer that suiseki were only all-natural stones. In an attempt to address and allow room for the acceptance of the age-old practice of working stones in Japan, in 1969, some ten years after declaring suiseki must be natural, Murata Keiji (Murata Kenji’s son) wrote the following in Juseki’s latest book, Encyclopedia for the Hobby of Suiseki:

“Ideally suiseki are natural stones, but there are cases where a certain amount of work is permitted. […] One should not manipulate the shape of the stone itself, but one could cut the bottom, or grind and polish in places. Depending on the extent of work done, such stones should be appreciated as suiseki. No matter how I think of it, however, I do not believe that stones with completely manufactured shapes are suiseki.”

The tone here is far more forgiving of non-natural stones than it was ten years earlier. He also defines suiseki in a very different way, broadening its scope even further.

<---- Encyclopedia for the Hobby of Suiseki by Murata Keiji, 1969 |

|

| |

|

|

Chart illustrating various stone practices that have influenced one another and merged to become “Contemporary Suiseki”, by Murata Keiji (1969)

|

By this time, however, a rift had already emerged. Suiseki enthusiasts were now largely split into two groups: those who adhered to the teaching that suiseki must be natural, and those who accepted that many were not. The former group is made up of enthusiasts who collect in rivers and mountains themselves, who would likely never buy a stone unless from a trusted friend. The latter group is made of up enthusiasts who buy stones from dealers, and often approach it the way one would approach art and antiques, by placing value on the history and provenance of a stone, rather than its natural qualities. Rather than following the centralized authority of the NSA, clubs were created in all parts of Japan with their own leadership. They often created their own rules- some insisting on natural stones only, collecting together in their local area and staging exhibitions of their finds, while others did not focus on field collecting or natural stones, instead focusing their interests on the broader cultural aspects of display and aesthetics, allowing worked stones or what would historically have been defined as bonseki. In fact, these separate tendencies long existed in Japanese stone appreciation, but now they were all forced under the same name of “suiseki”, and people still debate today what is the correct and incorrect approach.

One of the earliest and most honest discussions of modern Japanese stone appreciation was published in 1962 by Ito Shunji, in his book The Hobby of Stones: How to Find and Create Suiseki and Daiseki. |

|

|

Ito was involved in organizing two of the most important stone exhibitions some 20 years before the NSA was even created, which were held at the temple Kan’eiji in Ueno in 1940 and 1941. He maintained the definition of suiseki as “stones displayed in suiban”, and was openly opposed to Murata including daiza stones and kiseki under the suiseki classification. He states that his personal preference is for natural stones, but offers this as a retort to Murata Kenji’s publication three years earlier that suiseki MUST be natural:

“ […] However, as the expression, ‘A thousand people, a thousand faces’ goes, people’s tastes and preferences are extremely varied and wide ranging, and there is no shortage of people who like stones that have been made even more than natural stones, and simply cannot get enough of them. A hobby is not something to force on people, and even if you try to force it in a particular way, in the end you cannot succeed. This is only my personal opinion, but even if you say, revere natural stones and do away with those manmade, you can find goodness in manmade stones, and feel in them a pleasure that cannot be had through natural stones. I do not think there is anything wrong with that.”

The underlined section is a direct quote of Murata’s text, and he is clearly voicing his disagreement. For better or worse, however, Ito’s book was published by Tokuma shoten, a publishing house that for a short time had a rivalry with Murata’s publishing company, Jusekisha. Both publishers released a number of books about stone appreciation, and an overview of their content reveals that they attracted people with very different ideas. The Muratas, however, were more deeply entrenched in the bonsai and suiseki worlds, and their message won out (Tokuma shoten’s window of publishing on stones would only last four years, whereas Juseki continues to publish even today). They would go on to define the conventional standards that eventually spread around the world, and dissenting opinions would fall by the wayside. Despite being a prominent leader at the time, Ito’s name is all but unknown in Japan today.

The Hobby of Stones: How to Find and Create Suiseki and Daiseki by Ito Shunji, 1962 |

|

|

Many more pages would be required to fully flesh out the evolution of the terminology used in Japan and the many different schools of thought that emerged in the 20th century, but let us return to the original question: Must a stone be natural to be considered suiseki? We have seen that throughout history both natural and manmade stones have long been appreciated and revered in Japan, and it was not until the 18th century that a clear appreciation of natural stones emerged. Even so, this was very different from suiseki as we know it today. The medieval world of manipulated bonseki and bonsan combined with the pre-modern world of natural kiseki in the mid-20th century, and eventually all came under the same blanket term, suiseki. However, these worlds had very different approaches to stones, and their ways of viewing them could not so easily be reconciled. By the time Chubachi declared suiseki must be natural in the 1930s, there was already a long tradition of manipulating stones that had endured in Japan for hundreds of years. The Muratas tried to maintain Chubachi’s position, but in light of the reality of the situation, had to tone down their rhetoric and allow for a certain amount of manipulation. They could not ignore or deny hundreds of years of bonseki history, nor should we ignore or deny this tradition today.

|

|

When we look at a stone displayed in a daiza or suiban, are we appreciating the natural features of the stone in-and-of themselves, admiring the forces of nature that brought them into existence? Or are we appreciating the grander, natural scene that those features suggest, allowing our minds to wander and our imaginations explore, whether the stone is completely natural or not? Does there have to be one and only one single way? Certainly, as we have seen, there has not been only one consistent school of thought on the subject in Japan.

Stone appreciation has been, from its earliest recorded days in Japan, an exercise of allusion. Suiseki is, in its ultimate form, an appreciation of nature, and it is there and only there IN nature that one can learn its ways. We can learn nothing of this by reading books, surfing the internet, or listening to “experts” tell us what is right and wrong.

|

|

|

Go to the mountains, go to the seaside, seek out waterfalls and mountain streams. Spend time there and learn the sound of wind blowing through trees, learn the ways of the tide, the crashing of water, and the refreshing feeling of mists washing over you. It is only by spending time in nature that you can make these things your own, and it is not until you have internalized the beauty of nature itself that you will look upon a stone and experience these sensations.

Questioning whether a stone has been worked or not is a fine exercise for beginners looking at exhibition displays, or considering buying a stone, but it is not until you allow your mind to move beyond this that the true beauty of suiseki can reveal itself. Go into nature and make yourself the tenkei. Revere the mountains and the ways that the seasons and light can transform them.

Then, whether a stone has been cut or worked or not, you can find yourself transported to any number of places in the natural world, even when you are not otherwise free to venture far from home.

Become the tenkei

|

|

|

|

|

Postscript : Despite grand statements made both in Japan and abroad, there is not now, nor has there ever been, one single, universally accepted definition of suiseki that has remained unchanged over time.

The above has been an attempt to articulate the complex reality of stone appreciation in Japan, where many different practices and schools of thought remain to this day. It is not a call for adherence, but for understanding.

The West need not set out to replicate any single set of Japanese “truths”, however they are understood, as already a certain culture of stone appreciation has firmly taken root in many places around the world.

One can only hope that now this culture continues to grow and flourish abroad in its own unique ways, as suits the desires and aspirations of those who find inspiration in the nature that surrounds them.

|

| |

|